INTRODUCTION:

Takayasu arteritis (TA) is a well-known yet rare form of large vessel vasculitis. It is a chronic progressive, inflammatory arteritis seen in young adults affecting large vessels, predominantly aorta and its main branches.

The diagnosis of TA has always been a challenge. By the time it is diagnosed, the patient usually suffers significant morbidity. This delay in diagnosis is attributed to the rarity and unfamiliarity of the disease, non-specific early symptoms and expensive imaging modalities to detect pre-stenotic stage1.

CASE REPORT

In this report, we present a case of a 24 year old woman who came to family medicine clinic with complaints of weight loss, dry cough and right sided neck pain since 3 months.

On examination there was tenderness noted at the level of right mid-cervical lymph node region.

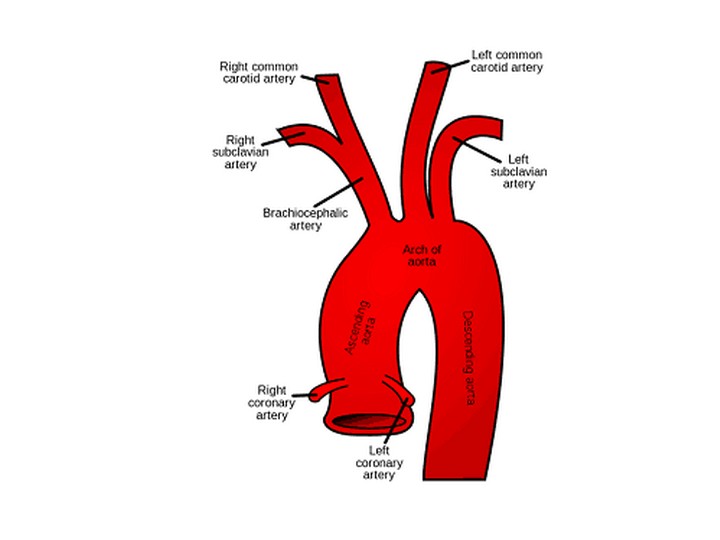

Investigations revealed mild anaemia with elevated Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and C-Reactive Protein (CRP). Chest X-Ray was normal. Ultrasonography(USG) neck revealed diffuse intimal thickening of right common carotid artery. Correlating the USG finding with pain and tenderness at carotid region, carotidynia was considered. Hence a possibility of large vessel vasculitis probably TA was suspected. However, clinically there was no discrepancy of blood pressures, all pulses were felt. No bruit or murmur was noted. Patient was referred to Rheumatology Outpatient Department for further evaluation.

CT-Angiography revealed diffuse circumferential wall thickening of Right Common Carotid Artery and bilateral pulmonary arteries. Based on the presenting symptoms, clinical findings, investigations and an abnormal angiogram a diagnosis of Takayasu arteritis (type 1) was done.

Her disease activity was assessed using ITAS (Indian Takayasu Arteritis Severity score) and patient was put on oral methotrexate 15 mg weekly along with oral prednisolone 40 mg per day. During her regular follow ups, the patient showed a significant improvement in her symptoms.

DISCUSSION:

TA is a chronic inflammatory disease of unknown aetiology affecting medium and large vessels. Although TA has been described worldwide, it occurs most commonly in Japan, China, India, and Southeast Asia. The first case of TA was described in 1908 by Dr. Mikito Takayasu (Japanese ophthalmologist) as a wreathlike appearance of blood vessels in retina. TA affects people in their 3rd-4th decade of life. Females are affected eight times more frequently than men. TA is characterized by granulomatous inflammation of the aorta and its major branches, leading to stenosis, thrombosis and aneurysm formation. The lesions of TA are segmental, patchy and involving all three layers of vessels.

The clinical manifestations follow two phases. In the early pre-pulseless phase, patients may complain of non-specific systemic symptoms including fever, weight loss, malaise, headaches, carotidynia, myalgia and arthralgia. In the later pulseless phase, commonly appearing months—years later, symptoms reflect end-organ ischemia and include limb claudication and neurological symptoms1. Carotidynia is a neck pain syndrome associated with tenderness over palpation of carotid bifurcation and it has been reported in 32% of patients with TA2.

The diagnosis of TA has always been a challenge. Multiple case reports and studies have shown that the diagnosis of TA is usually delayed from 10 months to 12 years, with 91% of patients reporting having seen at least one physician before diagnosis.1 By the time of diagnosis, the patient usually has already suffered significant morbidity.

This delay of diagnosis can be attributed to a few factors. First, both the early and late manifestations of TA are not specific; Laboratory findings include acute-phase reactant markers or ESR, which are not specific for TA; ACR( criteria to diagnose TA comprises components mainly of stenotic lesions and its manifestations reducing its sensitivity to TA in its pre-pulseless phase.

The 1990 ACR criterion for the classification of TA [Table 1] remains the most widely applied [4] criterion for diagnosis of TA. .The presence of three or more out of the six criteria is known to have a sensitivity of 90.5% and specificity of 97.8%.

| 1. | Age of onset ≤ 40 |

| 2 | Limbclaudication |

| 3 | Diminished brachial pulse |

| 4 | Difference of > 10 mmHg systolic pressure between arms |

| 5 | Bruit over the subclavian artery or aorta |

| 6 | Abnormal Angiogram |

| For diagnosis ≥ 3 criteria should be present (Sensitivity: 90.5%, specificity : 97.8%) |

| Sensitivy and specificity of various criteria in diagnosis of TA in clnically and angiographically proven 106 Indian patietns of TA | ||

| Criteria | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) |

| Ishikawa | 60.4 | 95 |

| American College of Rheumatology | 77.4 | 95 |

| Sharma et al. | 92.5 | 95 |

Our patient did not meet these criteria. This could be because it mainly comprises of components of pulseless phase of the disease; However, [5]Suri & Sharma criteria(1995) for TA was satisfied confirming the diagnosis.

Our case also highlights the fallacy in ACR criteria to identify TA in its pre pulseless phase. Adoption of Suri & Sharma criteria(1995) may prevent under diagnosis of TA.

Considering the progressive nature of the disease leading to significant morbidity due to target organ damage early diagnosis and treatment initiation is highly imperative to halt the disease activity thereby reducing significant morbidity.

Even though Non-invasive imaging modalities like, MR arteriography (MRA)[7], CT angiography (CTA) and positron emission tomography with 18F-FDG (FDG-PET), can help in diagnosis of TA early in the pre-stenotic phase, they are also very expensive and are not readily available in most of the hospitals. Therefore, the most crucial factor of early diagnosis is the physician’s awareness of the clinical findings.

CONCLUSION

Therefore, Carotidynia alone or with raised inflammatory markers in a young patient without risk factors for arteriosclerosis should alert the clinician to the possibility of arterial pain and subsequent large vessel vasculitides such as TA. Early recognition and initiation of treatment is paramount in managing TA to prevent morbidity. Suri and Sharma criteria(1995) may be recommended to diagnose TA in its pre-pulseless phase.

REFERENCES

1. Nazareth R , Mason JC . Takayasu arteritis: severe consequences of delayed diagnosis. QJM 2011;104:797—800.doi:10.1093/qjmed/hcq193

2. Zeina AR, Slobodin G, Barmeir E. Takayasus arteritis as a cause of carotidynia: clinical and imaging features. Isr Med Assoc J 2008; 10:158—9.

3.Keser G , Direskeneli H , Aksu K . Management of Takayasu arteritis: a systematic review. Rheumatology 2014;53:793–801.doi:10.1093/rheumatology/ket320

4. Arend WP , Michel BA , Bloch DA , et al . The American College of rheumatology 1990 criteria for the classification of Takayasu arteritis. Arthritis Rheum 1990;33:1129–34.doi:10.1002/art.1780330811

5. B.K. Sharma, S. Jain, S. Suri, F. Numano, Diagnostic criteria for Takayasu arteritis, International Journal of Cardiology,Volume 54, Supplement 2,1996,Pages S141-S147, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0167-5273(96)88783-3

6. Clinical manifestations of Takayasu arteritis in India and Japan--new classification of angiographic findings.Moriwaki R, Noda M, Yajima M, Sharma BK, Numano F Angiology. 1997 May; 48(5):369-79.

7.Magnetic resonance imaging of large vessel vasculitis. Atalay MK, Bluemke DA Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2001 Jan; 13(1):41-7

7. Takayasu's arteritis and its therapy. Shelhamer JH, Volkman DJ, Parrillo JE, Lawley TJ, Johnston MR, Fauci AS Ann Intern Med. 1985 Jul; 103(1):121-6.

| YOUNG DOCTORS MOVEMENT |STATE LEADERS | FMPC 2019 | FMPC 2022

| AFPI

© All rights reserved 2020. Spice Route India 2020

Contact us at TheSpiceRouteIndia@gmail.com